Tuberculosis may not be the curse it was before the era of antibiotics, but treatment is still long and tedious and, with the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains, the TB threat is rising again, killing 1.6 million people worldwide in 2021.

Current treatment regimes involve taking a cocktail of four antibiotics for six months. This long time frame and toxicity of the drugs reduce patient compliance leading to failed treatment, relapse and the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria. Because of this, better treatment options are needed.

However, to create better treatments, researchers need to understand how current antibiotics kill TB. TB bacteria, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, live inside the patient’s cells. However, cells have many compartments. It is currently unknown whether the bacteria and the antibiotics occupy the same compartments and how those compartments could affect drug effectiveness. Understanding this is critical to optimising the effectiveness of these drugs.

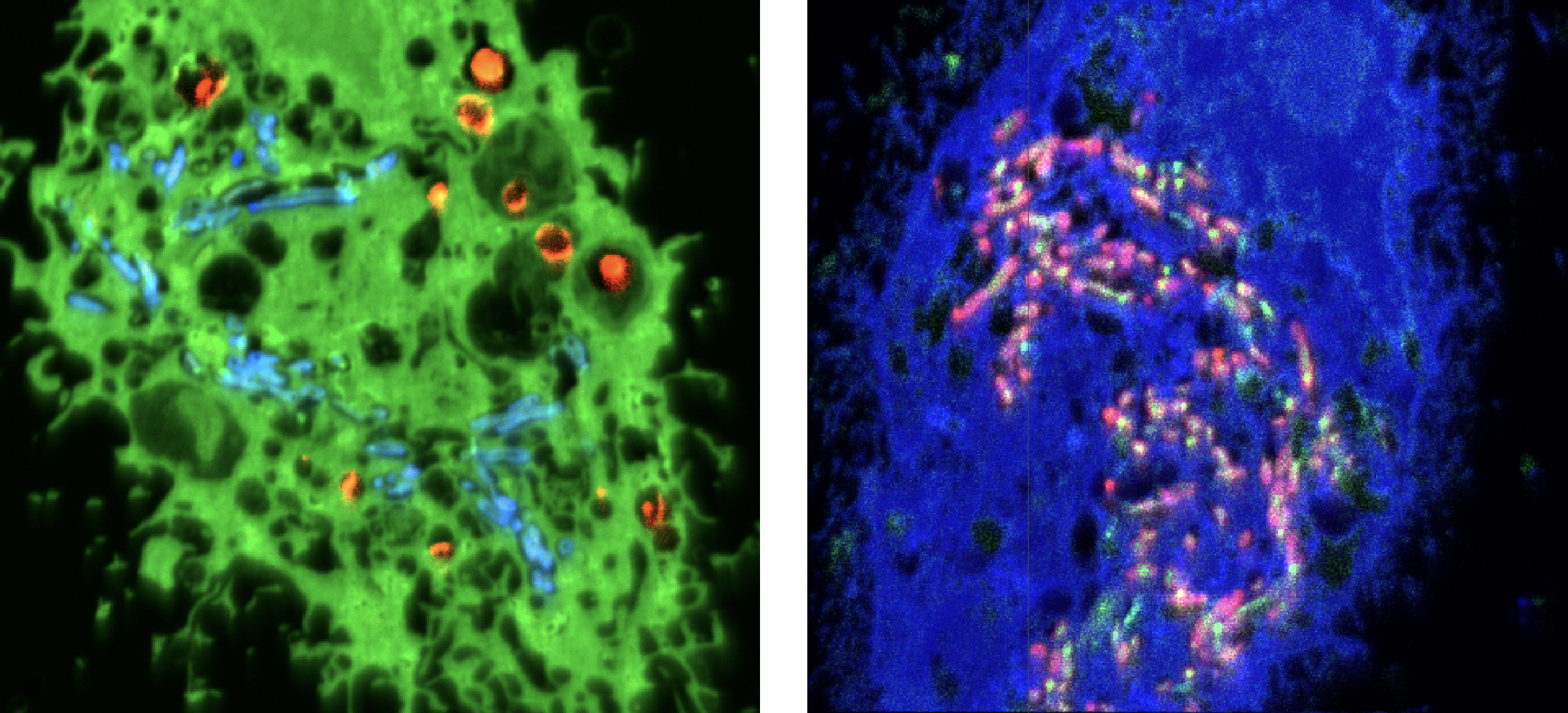

Researchers from the University of Western Australia, Hong Kong, the UK and Switzerland, have developed a new method that combines correlative light, electron and ion (nanoSIMS) imaging that allows researchers, for the first time, to see where the bacteria and antibiotics are located in the cells. This has allowed them to decipher how different intracellular micro-environments affect the action of the TB drugs.

NanoSIMS images of two TB-infected cells from the study. Left: pyrazinamide (blue) accumulated in TB-bacteria and bedaquiline (orange). Right: pyrazinamide (pink) accumulated in TB-bacteria and more disperse bedaquiline (green).

Different cellular compartments have different properties, such as acidity or the presence of enzymes, that could degrade or enhance the drugs. Researchers revealed that pyrazinamide, one of the antibiotics used in TB treatment, could more effectively target and kill the bacteria inside acidic cellular compartments. They also found that another of the antibiotics, bedaquiline, accumulates in the fat droplets used as a food source by TB bacteria, potentially facilitating drug uptake. Bedaquiline’s effectiveness was found to be influenced by the fat metabolism of host cells. The team also revealed that the two antibiotics work synergistically, with bedaquiline improving the ability of pyrazinamide to target TB bacteria.

The researchers found considerable variability in where the bacteria reside, even in adjacent cells. They were also surprised to find that pyrazinamide is not distributed consistently within cellular compartments but, rather, it accumulates within specific intracellular bacteria, being present in one bacteria but

not in its neighbour.

These differences in drug accumulation highlighted that antibiotic targeting of intracellular pathogens remains a complex puzzle, one that correlative microscopy is helping to solve.

This new correlative microscopy method combined with research findings opens the door to further work into how antibiotics act inside the cell. It also opens avenues for the development and implementation of efficient, short and more patient-friendly therapeutic alternatives for tuberculosis, which are desperately needed worldwide.

D. Greenwood et al., Science 2019

DOI: 10.1126/science.aat9689

P. Santucci et al., Nature Communications 2021

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-24127-3

Chest X-ray of child showing patchy infiltration of tuberculosis at right middle lung

June 7, 2023