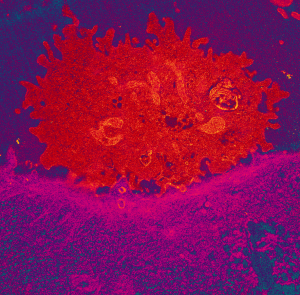

Colour-enhanced TEM image of a killer cell (red) attaching to cancer cell (pink).

Antibodies designed to attack cancers stick to particular proteins on the surface of the tumour cells and cause these cells to die. This occurs via a process called natural killer cell-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC). The more protein molecules there are on the surface of the cell the more places there are for the antibodies to stick, making the treatment more effective.

These protein molecules normally carry signals from the outside of the cell to the inside. Prochlorperazine was found to temporarily block the movement of these proteins into the cells leaving more on the surface where they can stick to the antibodies resulting in increased cell death. By combining antibodies and prochlorperazine, the researchers have also shown that the current variations in treatment effectiveness can be overcome.

Transmission electron microscopy conducted by Prof. Rob Parton and James Rae at our facilities at the University of Queensland was used to show the changes in movement of surface proteins into the cell.

“The anti-nausea drug works by changing the surface of the tumour cells so that existing cancer drugs which target tumours are better able to interact with the immune system,” Dr Simpson said.

“The result is that cancer cells become sitting targets that can no longer escape the immune system. “We observed a process we haven’t seen before and which increased the ‘natural killer’ immune cells’ ability to attach to, and kill the cancer. It is almost as if the killer cells become zipped to the tumour cells.”

Prochlorperazine, combined with existing cancer drugs like cetuximab, trastuzumab (Herceptin) and avelumab and was studied on tumours from head and neck, breast and metastatic colorectal cancers in mice. This resulted in the disappearance of all the tumours from ten mice with head and neck cancer. Dr Simpson was curious to see what would happen if they re-introduced the same cancer back into the mice four weeks later. “Amazingly, their cancer was rapidly eliminated – as if the new combination, in addition to being more effective, was also able to teach the immune system how to better recognise cancer cells,” Dr Simpson said.

The team’s long-term vision is to use this approach to not only clear a patient’s cancer in the immediate term, but to prevent their cancer coming back in the future by establishing protective ‘immune memory’.

Part of the UQ research team who conducted the studies

June 25, 2020