Most venomous animals use their venom for either predation or defence. Venoms for predation generally contain toxins that quickly paralyse prey, while defensive venoms contain pain-causing toxins to fend off predators. Some however, use their venom for both purposes and can control which toxin combinations to use in a specific situation.

How the different toxins are produced, stored and delivered has been studied in the red-headed centipede (Scolopendra morsitans) by a research team led by Dr Vanessa Schendel and Dr Eivind Undheim. A combination of 3D electron microscopy and 3D mass spectroscopy imaging at our University of Queensland facility revealed the detailed cellular anatomy and complex distribution of the different venom components within the centipede’s relatively simple venom gland. This shed light on how S. morsitans can fine-tune the secretion of different combinations of its multiple venom components.

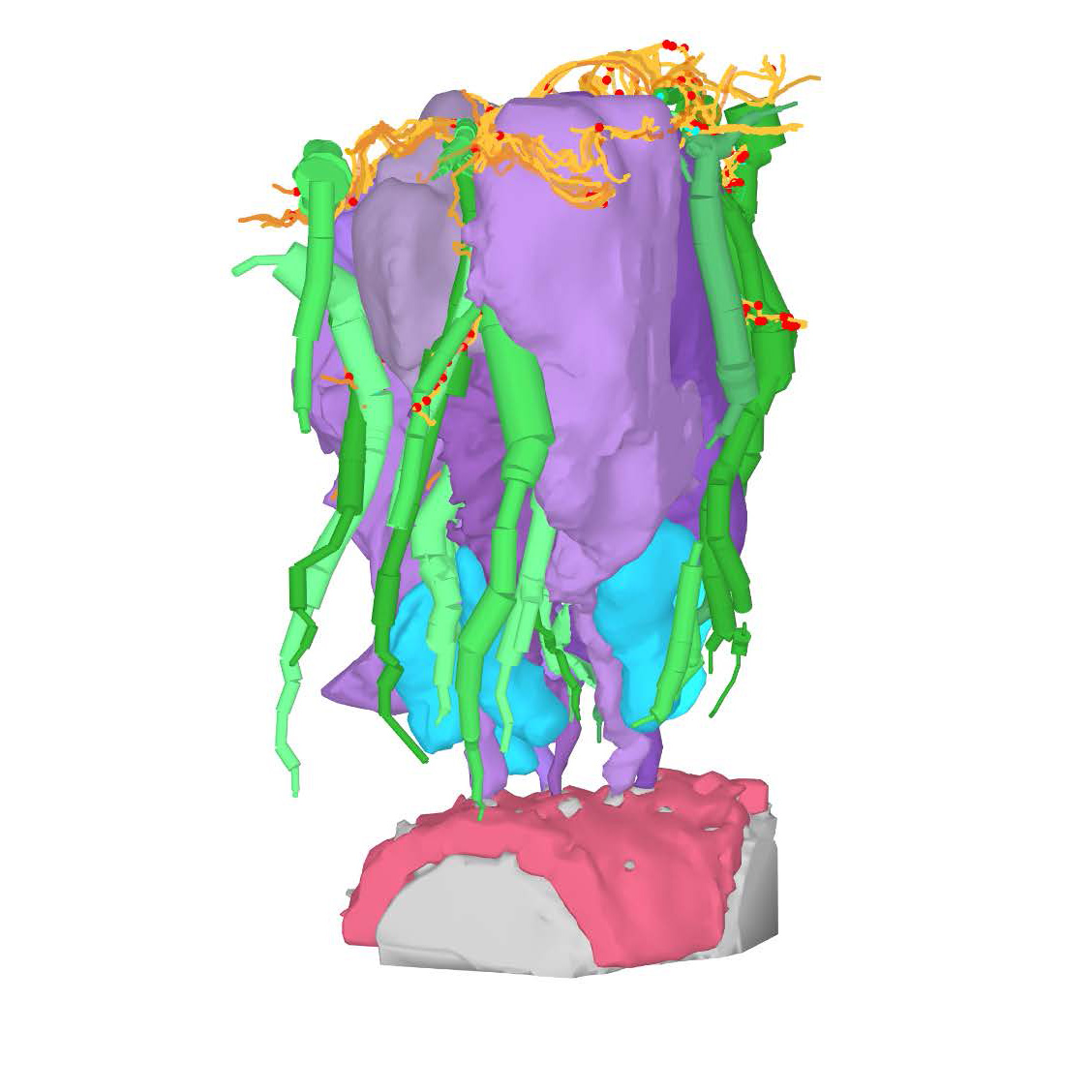

3D-EM reconstruction of toxin-producing cells, nerves and muscle fibres in a centipede

The 3D mass spectroscopy imaging showed that the centipede stores some of its toxins in different parts along the length of the venom gland. The team also discovered that there are pairs of cells that release their toxins by one of two mechanisms. One cell type is surrounded by muscle fibres and nerves which, when triggered, cause the venom to be squeezed out. The other cell type appears to respond to hormones or neurotransmitters that cause granules full of venom components to fuse with the cell membrane and release their contents into the venom duct. These processes enable different types of environmental stimuli to trigger release of venom profiles appropriate for the situation.

This rich body of work was recently published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

V. Schendel et al., Nature Ecology & Evolution 2024

DOI: 10.1038/s41559-024-02556-9

3D imaging mass spectroscopy of a centipede venom gland showing different distribution of various toxins along its axis.

December 16, 2024