The site comprised a series of retaining walls associated with gardening activities along with a network of stone arrangements, shell arrangements, rock art and a mound of dugong bones. Soils from the site showed definitive evidence for intensive banana cultivation in the form of starch granules, banana plant micro-fossils and charcoal. The team also found stone flake tools with plant residues along their cutting surfaces. Light microscopy at our ANU facility, the Centre for Advanced Microscopy, was used to further investigate these items, helping to identify the species the starches and micro-fossils came from.

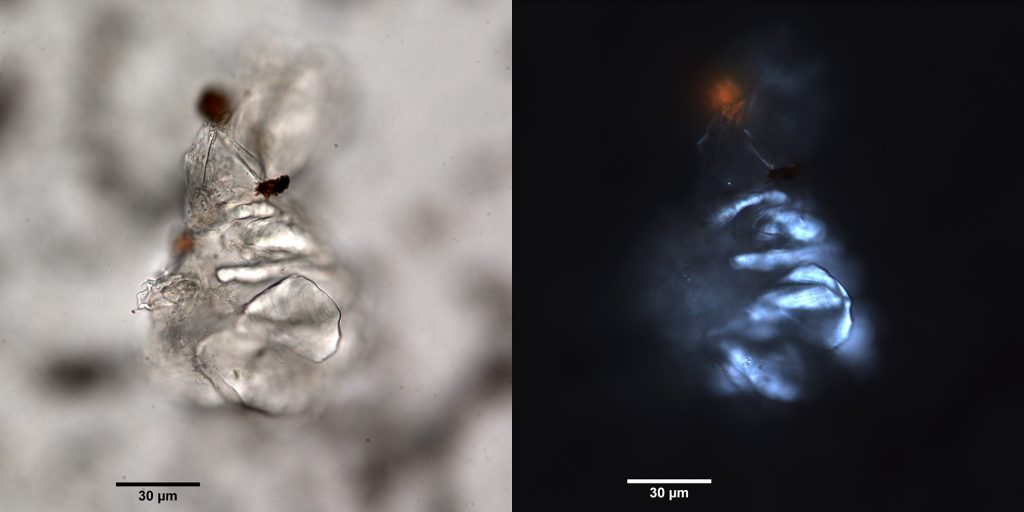

Clump of ancient banana starch from around 1300 years ago viewed with normal and polarised light microscopy. By Robert N. Williams

Lead researcher, Sydney University Kambri-Ngunnawal scholar Robert Williams, says the findings help dispel the view that Australia’s first peoples were “only hunter gatherers”.

“The Torres Strait has historically been seen as a separating line between Indigenous groups who practiced agriculture in New Guinea but who in Australia were hunter gatherers,” Mr Williams said.

“Our research shows the ancestors of the Goegmulgal people of Mabuyag were engaged in complex and diverse cultivation and horticultural practices in the western Torres Strait at least 2,000 years ago. So rather than being a barrier, the Torres Strait was more of a bridge or a filter of cultural and horticultural practices going both north and south. The type of banana we found on Mabuyag appeared much earlier on New Guinea, which was a centre of banana domestication.”

“What we’re seeing here is an Indo-Pacific horticultural tradition based primarily on things like yams, taro and banana and important fat and protein elements in the form of fish, dugong and turtle, these people had a very high-quality diet,” Mr Williams said.

“Food is an important part of Indigenous culture and identity and this research shows the age and time depth of these practices. I hope it will spark interest in these food traditions and might move people back towards them.”

Mr Williams said the charcoal found at the site indicated burning for gardening activities. Excavated charcoal provided dates for the finds through radiocarbon dating. Co-researcher Dr Duncan Wright said the Torres Strait region was a place where local innovations took place.

“The age of the banana propagation is also very significant. It’s not something we expect to see in continental Australia and this is the earliest well dated evidence for plant management in Torres Strait,” Dr Wright said. “At the time I thought it was odd to see cultivation in a landscape otherwise set aside for ritual activities. Now we know why, the retaining walls were part of a much older phase of activity at Wagadagam.”

As a descendant of the Kambri Ngunnawal peoples, Mr Williams said he was mindful of how his research could affect a first nations’ community.

“Historically, culture has been appropriated by non-Indigenous archaeologists and anthropologists, so it was really important for me to make a connection with the people in this community and ensure they understood the research really belongs to them.

“I hope this work is something the community can be really proud about. It demonstrates through clear evidence the diversity and complexity of early horticulture in the western Torres Strait.”

Mr Williams is the lead author on the research published in Nature, Ecology and Evolution. He did his Masters in Archaeology at ANU and is currently completing a PhD in the Department of Archaeology at Sydney University.

“This paper is led by a First Australian author. It’s another big achievement for Robert, whom I suspect will play an important role in the discipline of Archaeology,” Dr Wright said. “His work makes a statement that goes beyond academia, representing a much-needed shift for the discipline where research into First Nations’ communities is led by First Nations’ peoples.

We acknowledge that the research took place on country belonging to the Goemulgal.

Robert N Williams et al., 2020, Nature, Ecology and Evolution, 4, pp1342–1350

November 12, 2020