Wilhelm’s story sounds unbelievable, and it starts with a school prank in Utrecht at the Technical High School. Someone had painted a caricature of their teacher on the blackboard. Young Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen was asked to identify which classmate did the drawing, but Röntgen remained silent and was discharged from school without a high school diploma. At that moment, it would have seemed unthinkable that in 1901 he would become the recipient of the world’s first Nobel Prize in Physics.

Portrait of Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen. Credit: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv

This anecdote, despite being told thousands of times, might not be true. According to Uwe Busch, X-ray biographer, and director of the Röntgen Museum in Remscheid, Röntgen did leave school without a high school diploma. However, it’s more likely that this prank was an embellishment added over decades of retelling.

Regardless of Röntgen’s start in life, he went on to be an exceptional researcher who changed medicine and engineering forever with the discovery of “X”-rays, as he called them – X for unknown. Because of his discovery, it is now possible to look inside the human body without having to cut it open, allowing doctors to examine millions of people; alleviating pain and suffering.

Röntgen was born on March 27, 1845, in Lennep, today’s Remscheid. At the age of 16, he developed a pipe-smoking machine with which it was possible to puff cigars particularly quickly. The invention was not a milestone in the history of engineering, but it clearly demonstrated his talent for engineering. Röntgen was not an entrepreneur, he was a tinkerer and tester, the type of person who likes to bring his ideas to life with his hands. His parents recognised this potential and encouraged Röntgen to pursue his interest in engineering, instead of taking over the family’s cloth-trading business.

During his high school days, Röntgen lived with the chemist Jan Willem Gunning, who gave him his first glimpse into the world of university research. While living together Jan, who was a lecturer at University of Utrecht, published a summary of his chemistry lectures and Röntgen’s interest in science was sparked. However, without a high-school diploma Röntgen could not attend University as a full student and pursue this interest. Instead he applied to a Polytechnic Institute in Zurich (later ETH) where he completed a degree in mechanical engineering which opened the door to a postgraduate degree in physics. In 1874, Röntgen moved to Strasbourg, followed by research posts in Hohenheim near Stuttgart, Giessen, and finally Würzburg, where Prince Regent Luitpold of Bavaria appointed him full professor in 1888 – all without a high school diploma.

A few years after moving to Würzburg in the winter of 1895 Röntgen set the milestone which will forever be associated with his name – the discovery of X-rays, also known as Röntgen Strahlen: a new kind of electromagnetic radiation.

During this time, Röntgen – like many other physicists before him – experimented with cathode radiation. Like other researchers, Röntgen observed the previously unknown rays. But unlike others, he did not dismiss the phenomenon as a curiosity and continued to pursue it meticulously.

He studied light and other emissions generated by discharging electrical current in vacuum glass bulbs with positive and negative electrical currents. These glass bulbs were called ‘Crookes tubes’ which when discharging displayed a fluorescent glow if a high voltage current passed through the “empty” space. Röntgen was particularly interested in cathode rays and in assessing their range outside of these tubes.

On the 8th of November 1895, in a moment of serendipity, as Röntgen was about to leave the room he noticed that a barium platinocyanide coated screen nine feet away from the tube was glowing, despite having shielded the tube with a heavy black cardboard. While other researchers had observed this effect before, none had investigated it, as it was further away than the cathode rays, which they were interested in, were thought to travel. He quickly proved that this induced fluorescence was caused by invisible rays originating from the Crookes tubes.

Wilhelm Röntgen’s laboratory at the University of Würzburg, where he made his discovery of x-rays.

Further experiments revealed that these invisible rays were able to pass through most substances, including soft tissue of a body, but less, or none, passed through dense materials such as bones and metals. Röntgen also discovered that these rays could be projected through objects and captured on photographic film. It is said that Röntgen didn’t leave his laboratory for the next six weeks even though his apartment was on a floor just above the lab.

One of his earliest photographic plates is a film of his wife Bertha’s hand with her wedding ring clearly visible. This X-ray image of a hand has become a symbol for a paradigm shift in medicine and the birth of radiology.

The bones of a hand with a ring on one finger, viewed through X-ray. Photoprint from radiograph by W.K. Röntgen, 1895. Credit: Wellcome Collection, Library no. 32971i

In January 1896, Röntgen presented his discovery at a meeting of the Würzburg Physical-Medical Society; the famous second photo of a hand was taken there. It belonged to the anatomist Albert Kölliker. However, this image is not, as is sometimes wrongly reported, the first X-ray image in the world. After that demonstration the X-ray machines spread like wildfire.

Health risks from the radiation were initially unknown. It seemed like a dream come true for doctors, it was possible view the internal workings of a patient without having to cut them open and cause harm. For the first time they were able to pinpoint foreign objects, such as projectiles from pistols, along viewing with bones, blood vessels, lungs, and even foetuses in the womb. This discovery created a new and powerful diagnostic tool.

Along with more obvious medical applications, X-ray machines were used everywhere from fairs, to excite audiences, and at shoe stores to check how far the toes reached in a shoe. This lead to a shifting understanding in both doctors and lay people alike of the importance of the unseen.

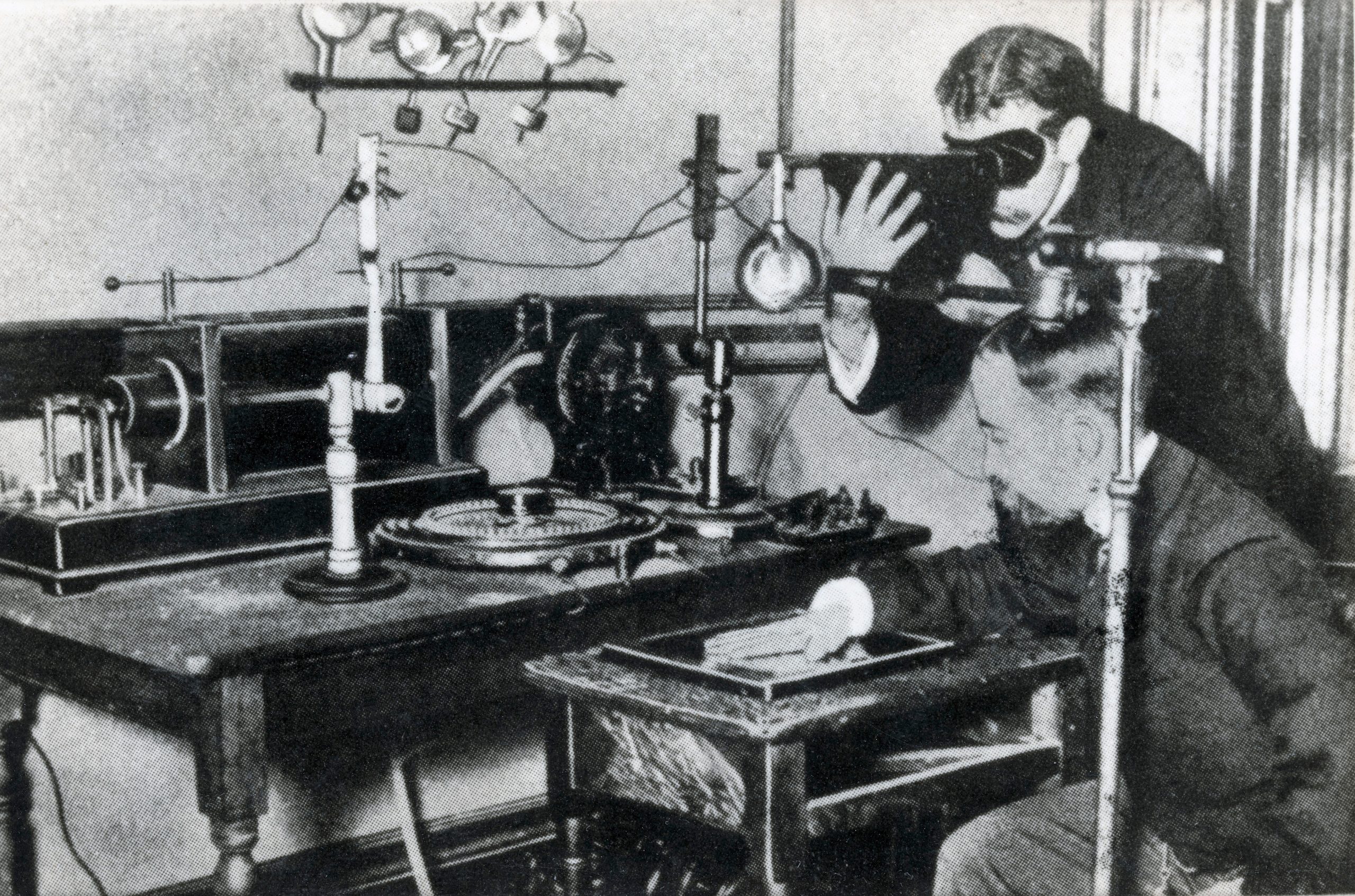

An early method of testing the output of X-rays using a fluoroscope is shown in this photograph. The body could be viewed through a fluoroscope without taking or developing time-consuming X-ray photographs. The X-rays instead fell on a screen which fluoresced immediately. This let the physician see the same thing as an X-ray photograph, or in this case use the fluoroscope to test the X-ray output. Credit: Science Museum, London

The popularity of X-rays shot Röntgen into the spotlight, a stardom he was reluctant to accept. He regularly escaped from events through the back door and fled from the hustle and bustle to hike in remote parts of the Swiss Alps to clear his head.

Over time, as symptoms and health issues started to arise from X-ray exposure the public started to distrust X-rays. Some feared that as X-ray technology expanded they would always be visible and ‘radiolucent’, and that nothing would remain private. Soon, doctors also started noticing that their patients’ hair fell after exposure to X-rays and some patients developed blisters and swelling. It wasn’t until later that the carcinogenic effects of X-rays began to reveal themselves.

125 years later, X-rays have been used to help treat millions of people and we now have a better understanding of their negative effects. Today, doctors are encouraged to only use X-rays when other examinations cannot be performed. Despite this, some believe doctors still rely too heavily on X-rays. This is what sparked the criticism by famous surgeon Ferdinand Sauerbruch: “Doctors, then as now, rely far too much on the images instead of examining their patients properly”. The numbers show that this tendency might be correct. More than 3.6 billion diagnostic X-ray are taken per year in around the world, with a global population of 7.8 billion that is a staggering number of X-rays.

If Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen had known the extent of his discovery that day when, by chance, he observed a glowing board while walking out of a room, it’s hard to know if he still would have chosen to pursue it. Röntgen never wanted the role of a science superstar and for the remainder of his years he avoided conferences. Instead, he took care of his sick wife until his death on February 10, 1923.

Today, Remscheid hosts the Deutsches Röntgen Museum close to Röntgen’s birth house with a lot of activities for schools and an exceptional exhibition. The 125th anniversary of the X-ray in 2020 has been postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic, while a new plan is being developed. Perhaps this is a fitting analogy for Röntgen’s life: the doors of Universities seemed closed to him due to his lack of school leaving certificate, yet with time, he managed to find a way.

Portrait of W.C. Roentgen after a photograph by Nicola Perscheld, 1906. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY 4.0

November 2, 2020