Critical illness caused by sepsis, trauma, cardiogenic shock, transplant rejection and severe haemorrhage is often complicated by the development of systemic inflammation and major organ injury. The lungs are particularly susceptible.

A severe reduction in blood flow (ischaemia) to the intestines can trigger blood clot formation in many other organs, including the lungs. The resulting lung injury develops into acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), from which around 90% patients die. No effective treatments or preventatives exist for this lethal condition: conventional anti-platelet therapies such as aspirin do not work. It is currently not clear how lack of blood flow to the gut causes blood clots in the lungs.

Understanding this process could lead to effective therapies to reduce remote clots in these critically ill patients and deliver more favourable outcomes.

Dr Yuping Yuan, Imala Alwis and colleagues working with Prof. Shaun Jackson at the Heart Research Institute at the University of Sydney used a combination of microscopy techniques to study clot formation in samples from ARDS patients and mice.

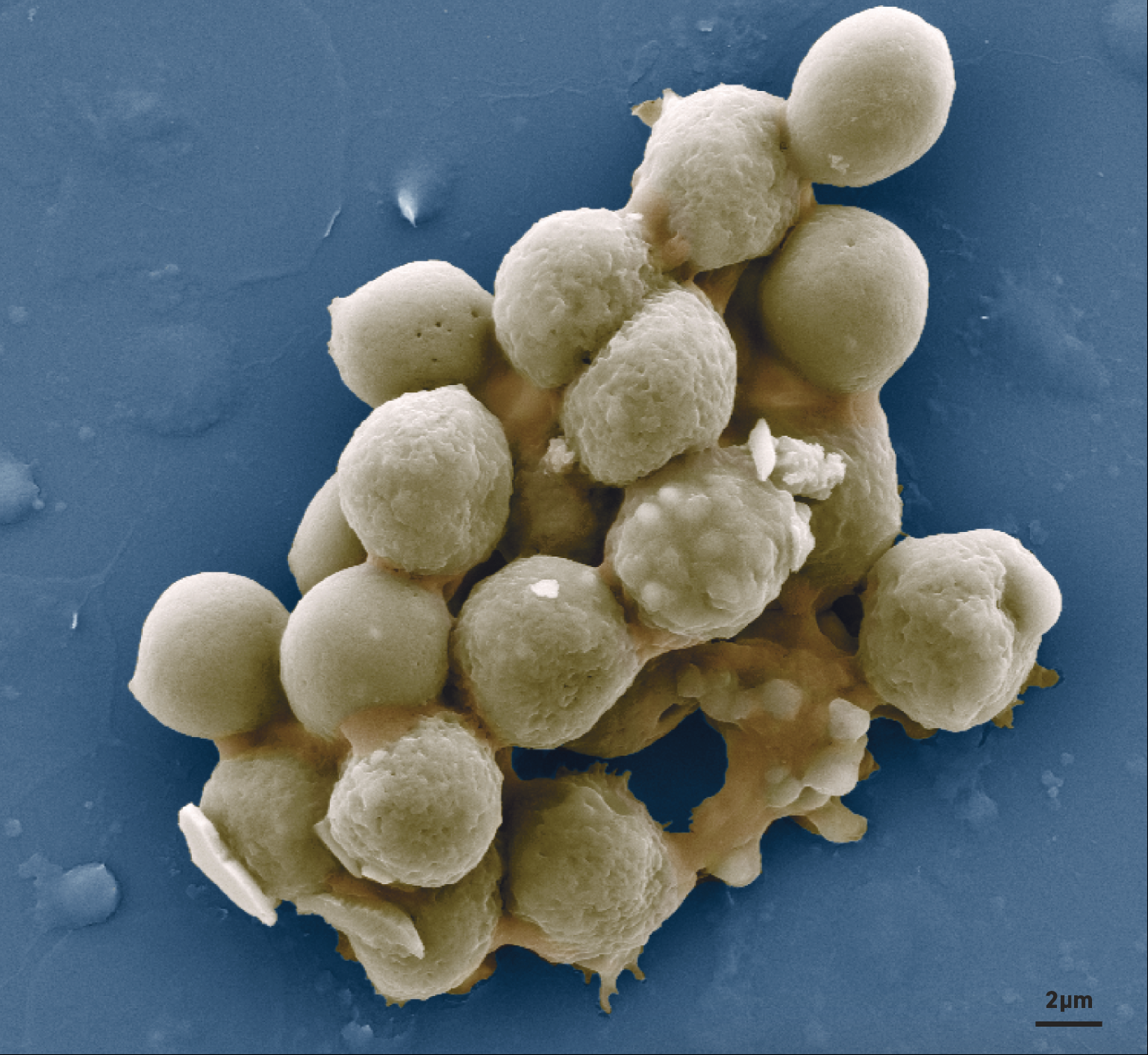

They showed that during gut ischaemia, clot-forming platelets die. Real-time confocal microscopy of the intestinal micro blood vessels during reduced blood flow revealed that rolling white blood cells called neutrophils grab and rip large membrane fragments from dying platelets as they pass by. These dead platelet fragments stick to adjacent neutrophils to form large aggregates that have the ability to obstruct blood flow. This previously unrecognised blood clotting mechanism links gut ischemia to remote lung injury. The team used scanning electron microscopy at Microscopy Australia’s University of Sydney facility to confirm the bridging capabilities of these dying platelet fragments in forming the neutrophil aggregates.

Although these clots are not amenable to conventional anti-platelet therapies, the protein cyclophilin D, which regulates cell death, was found to prevent neutrophil aggregation and clot formation in the lungs. This therefore identifies a new target pathway for potential drug therapies.

This newly identified clotting mechanism could lead to development of effective therapies that target lung clots in critically ill patients. This could save up to 12,500 lives per year in Australia alone.

July 24, 2017